M. John Harrison's fantastical conurbation Viriconium, or The Pastel City first appeared in the early 80s as an update of Gormenghast-style fantasy, but Harrison's Viriconium cycle of stories is poetic and strange enough to defy easy catagorisation. In this graphic novel, adapted from the short fiction (published in the collection by Fantasy Masterworks, no. 7) the city is re-named, a fact central to the plot, such as it is, which appears to concern an ancient weapon, an attempt to assassinate a member of the city's ruling class and a poet troubled by nightmare visions. The city exists as a sort of troubled vignette of a decaying future, but in fact it isn't placed in a historical context at all. Harrison has said that everything glimpsed in Viriconium is based on stuff that was already happening in Thatcher's Britain - the urban decay and sense of ruined empire was already present at this time in the blasted industrial landscape of the 1980s, and Viriconium, then, is an inner world to which we can retreat, which is changing all the time.

This story concerns also (appropriate to the time of year) a bizarre arcane ritual, called The Luck in the Head. The artist was one Ian Miller, (who previously worked with Ralph Bakshi, who made Lord of the Rings - the crappy animated version). He has rendered the scenes in a style faithful to the original story - at least how I imagined it would be. His drawing is impressionistic and probably completely uncommercial. Ironically this comic has little in the way of words or explicatory dialogue for an adaptation.

Author Mick Harrison himself appears in one scene, seated in a cafe eating gooseberries soaked in gin, in the part of one Ansel Verdegris, mad poet of the city, another conspirator in the plot. I don't think it would be giving too much away to say that this plot is doomed to fail, miserably and comically. Is Harrison trying to say something about narrative itself in Modern fiction?

The Luck in the Head is a dark and troubling book. It opens a door to a world not quite anything like our own.

Thursday, 30 December 2010

Monday, 20 December 2010

Film Club: Drowning by Numbers (1988)

Peter Greenaway composed the film for Michael Nyman's 1988 soundtrack Drowning by Numbers; or was it the other way around? (I heard Nyman's melodic, Mozart-inspired minimalist score before I saw the pictures, and so had to make my own story up in my head before I knew what the movie would be like). In the event the film was very nearly not a disappointment; it would have had to be very good indeed to live up to the soundtrack, and indeed it was, on a big screen (projector; traditionalist) with good sound and good company (and a good wine) cinema is improved immeasurably. David Lynch has said that it does not matter what form film takes on in the future, as long as these things are present (he did not mention the wine specifically, I do not think that they will serve you wine in most cinemas, but you may be lucky enough to have a projector in your home, in which case it is permissible to encourage your guests to bring a bottle).

|

| Madgett's breakfast |

The director appears to be playing games too - all those that appear in the film, such as 'Hangman's Cricket' were made up for the movie. There almost appears to be some sort of postmodern business going on - eventually life and death themselves become games, and the viewer is invited to arrive at their own interpretation of what it is that it all means; all this painterly symbolism. The cast are actually very good, but the objects and symbols seem to express more than the nuances of their characters ever really could.

There are several lecherous old men in the story. Maidens are pretty, and frolic in the Southwold countryside. We are almost in the world of fairy-tale here, but there is no moral to the story. Ultimately we get up to 100 and the film ends - what more can it do? 'Once you've counted 100, the rest are all the same,' says someone. It's funny - the film is often funny, and sometimes tragic. Bit like life, really.

images: http://petergreenaway.org.uk

Sunday, 5 December 2010

A Thriller Chiller

|

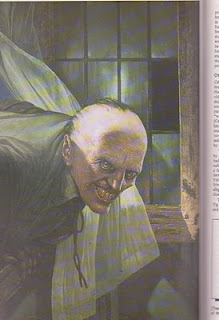

| illustration by Lee Gibbons |

His influence is still felt. Lovecraft knew, for instance, that the most terrifying part of the tale is that before the cause of the terror is revealed, and that fire is not as terrifying as ice. After the Monster is shown, in fact it can seem a bit silly, no more than a cheap special effect. Stephen King and Clive Barker are low-rent imitations next to him, relying on the sensational. Yes, those stories are horrible, once the 'monster' element in them is revealed, but it's a different kind of fear.

He writes everything as if it's absolutely factual. He was interested in forbidden knowledge; he has a way of occasionally inserting something that just conceivably could be true, and this is what gives us pause to question our assumptions about the world. He was clever. He knew how to play on subconsciousness - for one thing, racial fears. He would have recognised King Kong for what it is.

He got many of his ideas in dreams. No writer conveys that feeling better than him. For me, he's also one of the only writers who truly nails the first-person-past-tense. Michel Houellebecq has written a pretty definitive introduction to him for anyone who wants the lowdown, and he seems to have been pretty unhappy, but there's also some of the guy's own material in the book, which would deserve to stand on it's own even if the man himself had been a three-legged Mexican nasal flautist.

I found these images, along with the extract, in an old Games Workshop manual (and how many writers can say they have one of them?), I will take them down if this offends anyone.

THE LAIR OF GREAT CTHULU

Tune: Chattanooga Choo-Choo

Pardon me boy,

Is this the Lair of Great Cthulu?

In the city of slime,

Where it is night all the time.

Bob Hope never went,

Along the road to Great Cthulu,

And Triple-A has no maps,

And all the Tcho-tchos lay traps.

You'll see an ancient sunken city where the angels are wrong.

You'll see the fourth dimension if you're there very long.

Come to the conventacle.

Bring along your pentacle;

Otherwise you'll be dragged off by a tentacle.

A mountain's in the middle, with a house on the peak:

A gnashin' and a thrashin' and a clackin' of beak.

Your soul you will be lackin'

When you see the mighty Kraken.

Oo-oo! Great Cthulu's starting to speak.

So come on aboard,

Along the road to Great Cthulu.

Wen-di-gos and dholes

Will make Big Macs of our souls.

Under the sea,

Down in the ancient city of R'lyeh,

In the lair of Great Cthulu,

They'll suck your soul away!

(Great Cthulu, Great Cthulu -

Suck your soul! -

Great Cthulu, Great Cthulu)

In the lair of Great Cthulu,

They'll suck your soul away.

(Here, there is an obligato saxophone solo, a-la Tex Beneke)

-Joe Carruth and Larry Press

Text & images © 1980-1983 Pentalpha Journal / Games Workshop

Reproduced under fair usage rules, please contact us to remove!

Friday, 26 November 2010

Bloomsbury by Lamplight, Denouement

The Hotel at Tavistock Square

It was built post war, so does that make it faux-deco? Could it be that already, in this period of austerity, people were harking back to jammier earlier times?

As we know, reader, there was no time in history when things were somehow more correct or morally upright than they are now, only periods of harmony and relatively good design. The deco era was eventually killed off by a surfeit of burnished wooden parts and gilt lines, or perhaps people just wanted something a little more functional and reliable. In any case, many of these sorts of detail are still visible in the Tavistock hotel.

These days, it would be a cheap place to come for a pint of IPA (at London prices). Afterwards, during the hours of daylight, you can go for a stroll through the pleasant green area outside - one of many around here.

War (what is it good for? Apparently nothing)

Around the park you can see where the original railings once ran. These must have been stripped out in the Great Iron Swindle of the Second War. Most of this metal, the story goes, so patriotically given up (a huge propaganda effort), ended up dumped in the Thames as un-usable. As historical portents go this seems a symbol of the kind of unpleasant future we were heading for, something the unadorned buildings and public spaces shorn of their trimmings tend to testify to... one in which people will be continually deluded into parting with any kind of precious metal they may have accumulated should they be fortunate enough.

You can say what you like about Britain in the 200 years or so pre-C20, in which public parks and (so-called) altruistic ventures like this one were popular, but there must have been at that time a great deal of, if not public spirit, then at least civic pride. I say so-called altruistic ventures because it seems to me that the kind of public spaces I'm taking about were good for everybody, and that the philanthropists who gave up their time, cash and land for such places - and built a fair sort of terraced housing for the workers they employed - were safe in the knowledge that they were giving something back, and fulfilling their part of the bargain with the land that had allowed them to become rich men. That 'social contract' was torn up now, in favour of blind patriotism, to pay for the wars of the 21st century - the irony being that it probably did no good at all, if indeed killing Germans can be construed as good.

You can say what you like about Britain in the 200 years or so pre-C20, in which public parks and (so-called) altruistic ventures like this one were popular, but there must have been at that time a great deal of, if not public spirit, then at least civic pride. I say so-called altruistic ventures because it seems to me that the kind of public spaces I'm taking about were good for everybody, and that the philanthropists who gave up their time, cash and land for such places - and built a fair sort of terraced housing for the workers they employed - were safe in the knowledge that they were giving something back, and fulfilling their part of the bargain with the land that had allowed them to become rich men. That 'social contract' was torn up now, in favour of blind patriotism, to pay for the wars of the 21st century - the irony being that it probably did no good at all, if indeed killing Germans can be construed as good. You can still see the stumps around any of our major towns, like cheery domestic reminders of the stumps on some of the veterans who came back from those wars. The ones here in Tav. Square have been replaced, with the effect of making the park about a foot smaller on each side. Nothing that is taken away can ever be restored without losing a little something.

If you think that this kind of argument is just dumb commie socialist thinking, and not particularly relevant in a discussion of a part of London lived in (historically, since it isn't homes any more) by fairly or very well-off people, then try to imagine a property developer today reconstructing a large area of the middle of one of our major cities and building a large public park for every dozen or so houses. More likely they would be packed in like our lives depended on it.

I am trying to establish an idea of the kind of world into which the Bloomsbury's of the tens and the twenties were born, and the kind of world in which they found themselves living only 20-30 years later. Not one that was wonderful, for sure, if one was lower class, but one in which the upper-middle could afford to be less mean, with class war still primarily a thing of the future.

The attitude of the Bloomsbury's towards the Second War appears to have been: Not again. Whilst the first one may have been a terrible thing against which those who did not fight were insulated to some extent, Vanessa and Clive Bell did lose a child, their eldest son Julian, to the Spanish Civil War. Mark Hussey has edited a volume of essays on Virginia Woolf's personal opposition to war, in both her fiction and nonfiction writing. Having said all that, they may have had vested interests: Leonard Woolf was a Jew. He and Virginia were both rumoured to be on a death list that would have been enacted had the mooted German invasion ever gone ahead.

Any cultural advantages we may have enjoyed in this country in the later part of the twentieth century are due entirely to the fact that this pogrom never took place.

Personally I have often thought that the rock band Queen is what popular culture would have looked like, and sounded like, had the Nazis won the Second World War. I cannot say why.

Leaving Tavistock Square

At the opposite end of the square there is even less left to find - one corner has been turned into a Starbucks now. The British Medical Association is next door. Charles Dickens used to have a house on this site. On the Seventh of July 2005, at this corner of Tavistock Square, a double decker bus exploded in a terrorist attack on London, the fourth and final of several devices that would go off on public transport that day. So it goes.

From where her bust stands, at the opposite corner of the square from where events on 7/7 took place, if she were to turn to her right Virginia might just be able to make out the British Telecom Tower (what Alan Moore re-dubbed in V for Vendetta as 'The Ear') - 'we are at least listening to you, if not actually watching you,' behing the implication here. It's little wonder that Thomas Pynchon found such paranoia present in this city to fuel his encyclopedic novel Gravity's Rainbow (published 1973. The tower was finished in 1966, though its existence remained an official 'secret' until the nineties, when it was finally allowed to appear on OS maps).

From where her bust stands, at the opposite corner of the square from where events on 7/7 took place, if she were to turn to her right Virginia might just be able to make out the British Telecom Tower (what Alan Moore re-dubbed in V for Vendetta as 'The Ear') - 'we are at least listening to you, if not actually watching you,' behing the implication here. It's little wonder that Thomas Pynchon found such paranoia present in this city to fuel his encyclopedic novel Gravity's Rainbow (published 1973. The tower was finished in 1966, though its existence remained an official 'secret' until the nineties, when it was finally allowed to appear on OS maps).On my particular pilgrimage Virginia Woolf was ultimately as elusive as another of Pynchon's characters, V, who is both woman and symbol, who may once have existed but ultimately affects us from the realm of the inanimate, to which all worlds, eventually, tend. Now, almost seventy years gone, Virginia exists in the mass consciousness on the written page, ethereal, not the electronic proof we demand of our present-day public figures (only one recording of her exists; it is well worth hearing). She might have been amused that people have seen fit to erect a work of statuary to her at all: 'if I had received that kind of adulation in my lifetime,' she might have said, 'I should have killed myself.'

Down the way, informal students sit gathered under the tarpaulin of a small café, smoking shishas. Many of them may not have heard of Virginia Woolf, but seventy years ago she wrote her thoughts down, and they are still present, in a real way, that I doubt any of our electronic media will be in a hundred years time. Informational entropy seems to have reached a near-maximum in the city: everyone is talking, but no-one is saying anything. Did she present a part of this, with her stream-of-consciousness, her constant talk about her self; or did she represent something different, a genius, someone for whom life was truly worth celebrating, for whom words were the medium?

I went to London to find her; she was not there. Anyone else who wants to look for her would be well advised to try somewhere else. The books would be a good place to start.

Wednesday, 17 November 2010

Bloomsbury by Lamplight, 2

Virginia Woolf is a tantalising figure, as close as she is, just out of reach - she died in 1941, at the age of 59, and had she lived a little longer she might have left more to the media age that we live in today than a handful of meandering novels, diaries and essays.

From 1904 to 1912 Virginia Stephen lived in Gordon Square, which she left following her marriage to Leonard Woolf (with whom she would ultimately found her own publishing house, the Hogarth Press). In 1924 the Woolfs returned to neighbouring Tavistock Square, in which she'd live until the outbreak of the Second World War, when they moved again to nearby Mecklenburgh Square. The Tavistock Hotel now stands on the site of the house.

In those days a publishing house would have been just this - a house with a printing press inside it.

In those days a publishing house would have been just this - a house with a printing press inside it.

In 1940 the house at Mecklenburgh Square was bombed, necessitating a move to the country. Poetically enough, as it turns out, the end of Virginia's association with the area also marked the beginning of her own end, as in 1941, in the darkest days of the war, suffering from depression again, she drowned herself in the River Ouse in Sussex.

Her literary afterlife began with her books falling out of fashion, lacking in relevance to the common reader, but, ironically, she was quickly rehabilitated by the kind of leftist critics who had rejected her, as one of the original names in feminist literature. In the sixties and seventies. Virginia became, if not a popular culture figure, than at least a cult figure.

Patti Smith has written poetry about her, and Nicole Kidman portrayed her on film. Along with Slyvia Plath she exerts a particular and almost unique kind of fascination. And yet, in an age where you can get cross-platform stars like Nick Cave reading their own book aloud on your iphone (and actually playing music to go with it as well), in which this kind of gimmick is almost expected of authors, Virginia exists, almost alone, on the printed page.

There is the work, the letters, and what nephew Quentin Bell told us in her biography, and another follow-up book about the Bloomsbury 'set'. Virginia's extensive diaries were published in an edition of five volumes from 1977-84. No doubt one could get as good an idea of what was going on behind these closed doors in Gordon Square in 1910 as you could about Lady Gaga from reading a modern day gossip column.

Gordon Square

The first house that we come to belonged to Virginia & her sister, Vanessa Bell, the painter (also her brother Adrian, who would, it's worth noting for fans of such footnotes, go on to become one of the first British psychoanalysts). Most of these houses seem to be offices or classrooms for the UCL today. The blue plaque on the door here commemorates not the prodigal Stephen children but their friend the economist Maynard Keynes, who lived here after them.

|

| 50 Gordon Sq. |

Keynes was an influential figure, a liberal thinker who invented Keynesian economics and had a building named after him at my old university for his trouble. He seems to have lived more-or-less openly as a homosexual until he met a ballarina, called Lydia Lopokova, whom he married in 1925, and thus became a more-or-less ordinary establishment figure.

Keynes essentially suggested that if there are not enough jobs to go round, the government should bury some dollar bills down a hole and pay men to dig them up. Some of my friends at Housman's bookshop would perhaps agree with this kind of keen thinking. Others might less kindly suggest we should bury Keynes down a hole.

Not far down, at number 50, another plaque mentions Virginia, Clive Bell and the Stracheys. Clive was an art critic and formalist who married Vanessa. He seems to have been, by all accounts, rather a prig, but perhaps he gets a thin crack of the whip by reputation as he was married to Vanessa Bell in only a legal sense for the majority of their relationship. Although they never divorced, they lived separately, had many other lovers, and allowed her daughter Angelica to grow up believing she was Clive's until the age of 17. Her real father, the painter Duncan Grant, another colourful character in the Bloomsbury tableaux, was a former lover of Maynard's!

Lytton Strachey was another author, one of ten surviving children, who wrote a satirical work of biography, Eminent Victorians, that laid some of the ground for Virginia's Orlando. He never married, but conducted affairs with Keynes and the artist Dora Carrington (allegedly), although, according to friends, he was more interested in her husband Ralph Partridge. After Strachey died, at 51, Carrington killed herself, seeing no reason to go on. Today she is perhaps best known for designing woodcuts for the Hogarth Press (and for being played on film by Emma Thompson).

Next: A stop at the Tavistock Hotel

Monday, 8 November 2010

BLOOMSBURY by LAMPLIGHT pt.1

Notes on a trip to London, 2.10.2010

|

| Housmans (Housmans.com) |

Housman's opened in 1945, when a wave of optimism about what was possible if we all 'pulled together' saw a brief turn towards socialism in this country, at a point when such thinking was popular. It seems to have been re-emerging, blinking and brushing the dust off, into fashion and people's consciousness at intervals, when the moment has allowed it, ever since that time.

A quick, cursory glance at the stand that holds those limited works of vitriol, comix and pamphleteering that we might for want of a better word term 'fanzines', reveals those that have been accepted for display to date back, mostly, to the nineties or earlier, suggesting that no one has seem fit to cull the stock since that time. One such august publication looks at the possibillity of global one-world government becoming a possibility in 1984, in line with Orwell's fictional depiction of that year. Might we be, it suggests, in the nineteen eighties, in a new age of austerity, echoing the spirit of fifty years earlier?

Up the road, twenty minutes away or a short hop by underground train or London taxi, art-deco lamps from the guilded age are burning in the foyer of the Tavistock Hotel, Bloomsbury.

Virginia Woolf was an English novelist, authoress of essays and exponent of modernism who killed herself in 1941 when she decided the modern world we had created was not worth living in any more. She was somewhat upper-crust: her mother seems to have been a model for Pre-Raphaelite painters including Edward Burne-Jones; her father Leslie Stephen was an editor and critic, which means that she would have grown up around the detritus of Victorian literary society. They were a large family; both parents had been married before, and both had children from an earlier marriage.

|

| Woolf's mother? |

Gordon Square is reached if one walks up Bloomsbury Street from Centre Point past the British Museum, turning right at Bedford Sq. past the unbelieveably Orwellian ('Ministry of Truth') menacing Senate House building, where the rather grand facades of Georgian terraces face on to green spaces in the shape of small parks, now closed up at night, which must have looked roughly the same in Virginia's time. But, by the end of her girlhood, it must have become quite clear to her that the world was changing in ways she never previously could have envisioned.

next: a trip around Gordon Square.

Wednesday, 27 October 2010

Credit Union

|

| Clouds over Braintree, 27.10 - almost made it worth going... |

As the banks and the money-grubbers have proven themselves - again - totally incapable of taking care of our savings, would it be such a crazy idea to suggest a credit union for Colchester? Then, rather than going into nebulous and nefarious projects in far corners of the world or banker's bonuses for supposedly conferring on us the benefit of their administration, the reward for our labour could go back into our own town, encouraging much needed urban regeneration. The union could provide jobs for local people who would take an interest in what they were being asked to do.

Very many people have theorised about what is wrong with the present system and what could be done with it, to the point of calling for armed revolution. It seems to me that if we were all to withdraw our money from the banks at the same time, the effect would be very much greater than any kind of massed protest might have otherwise, and hit those who would appoint themselves the management of humanity PLC where it hurts - in the wallet! The emphasis would then be on us to do something constructive with that capital, which might force us to take a bit of responsibility for our own lives, rather than wallow in the collective apathy to which corporate interests have lulled us. It is scary, but we could do it...

Monday, 4 October 2010

JUNO, continued

At first what was it but an apprehension sweet as far bird song - a tremulous thing - an awareness that fate had thrown them together; a world had been brought into being - had been discovered? A world, a universe over whose boundaries and into whose forests they had not dared to venture. A world to be glimpsed, not from some crest of the imagination, but through simple words, empty in themselves as air, and sentences quite colourless and void; save that they set their pulses racing.

Theirs was a small talk - that evoked the measureless avenues of the night, and the green glades of noonday. When they said 'Hullo' new stars appeared in the sky; when they laughed this wild world split its sides, though what was so funny neither of them knew. It was a game of the fantastic senses; febrile, tender, tip-tilted. They would lean on the window-sill of Juno's beautiful room and gaze for hours on end at the far hills where the trees and buildings were so close together, so interwoven, it was impossible to say whether it was a city in a forest or a forest in a city. There they leaned in the golden light, sometimes happy to talk - sometimes basking in a miraculous silence.

Was Titus in love with his guardian, and was she in love with him?

Theirs was a small talk - that evoked the measureless avenues of the night, and the green glades of noonday. When they said 'Hullo' new stars appeared in the sky; when they laughed this wild world split its sides, though what was so funny neither of them knew. It was a game of the fantastic senses; febrile, tender, tip-tilted. They would lean on the window-sill of Juno's beautiful room and gaze for hours on end at the far hills where the trees and buildings were so close together, so interwoven, it was impossible to say whether it was a city in a forest or a forest in a city. There they leaned in the golden light, sometimes happy to talk - sometimes basking in a miraculous silence.

Was Titus in love with his guardian, and was she in love with him?

p.88, Titus Alone, by Mervyn Peake, 1959

Saturday, 18 September 2010

JUNO, pt.1

Titus withdrew his face which had been crushed against a naked shoulder, and got dizzily to his feet, and as he did so he saw that the ladies eyes were fixed upon him. Even in her horizontal position she was superb. Her dignity was unimpaired. When Titus reached down to her with his hand to help her she touched his finger-tips and rose at once and with no apparent effort to her feet, which were small and very beautiful. Between these little feet of hers and her noble, Roman head, lay, as though between the poles, a golden world of spices.

Someone bent over the boy. It was the Fox.

'Who the devil are you?' he said.

'What does that matter?' said Juno. 'Keep your distance. He is bleeding... Isn't that enough?' and with quite indescribable élan she tore a strip from her dress and began to bind up Titus's hand, which was bleeding steadily.

'You are very kind,' said Titus.

Juno softly shook her head from side to side and a little smile evolved out of the corner of her generous lips.

'I must have startled you,' said Titus.

'It was a rapid introduction,' said Juno. She arched one of her eyebrows. It rose like a raven's wing.

Someone bent over the boy. It was the Fox.

'Who the devil are you?' he said.

'What does that matter?' said Juno. 'Keep your distance. He is bleeding... Isn't that enough?' and with quite indescribable élan she tore a strip from her dress and began to bind up Titus's hand, which was bleeding steadily.

'You are very kind,' said Titus.

Juno softly shook her head from side to side and a little smile evolved out of the corner of her generous lips.

'I must have startled you,' said Titus.

'It was a rapid introduction,' said Juno. She arched one of her eyebrows. It rose like a raven's wing.

p.51, Titus Alone, by Mervyn Peake, 1959

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)