M. John Harrison's fantastical conurbation Viriconium, or The Pastel City first appeared in the early 80s as an update of Gormenghast-style fantasy, but Harrison's Viriconium cycle of stories is poetic and strange enough to defy easy catagorisation. In this graphic novel, adapted from the short fiction (published in the collection by Fantasy Masterworks, no. 7) the city is re-named, a fact central to the plot, such as it is, which appears to concern an ancient weapon, an attempt to assassinate a member of the city's ruling class and a poet troubled by nightmare visions. The city exists as a sort of troubled vignette of a decaying future, but in fact it isn't placed in a historical context at all. Harrison has said that everything glimpsed in Viriconium is based on stuff that was already happening in Thatcher's Britain - the urban decay and sense of ruined empire was already present at this time in the blasted industrial landscape of the 1980s, and Viriconium, then, is an inner world to which we can retreat, which is changing all the time.

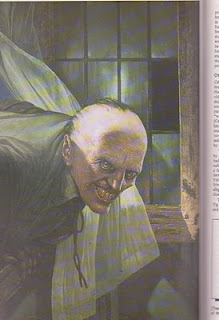

This story concerns also (appropriate to the time of year) a bizarre arcane ritual, called The Luck in the Head. The artist was one Ian Miller, (who previously worked with Ralph Bakshi, who made Lord of the Rings - the crappy animated version). He has rendered the scenes in a style faithful to the original story - at least how I imagined it would be. His drawing is impressionistic and probably completely uncommercial. Ironically this comic has little in the way of words or explicatory dialogue for an adaptation.

Author Mick Harrison himself appears in one scene, seated in a cafe eating gooseberries soaked in gin, in the part of one Ansel Verdegris, mad poet of the city, another conspirator in the plot. I don't think it would be giving too much away to say that this plot is doomed to fail, miserably and comically. Is Harrison trying to say something about narrative itself in Modern fiction?

The Luck in the Head is a dark and troubling book. It opens a door to a world not quite anything like our own.

Thursday, 30 December 2010

Monday, 20 December 2010

Film Club: Drowning by Numbers (1988)

Peter Greenaway composed the film for Michael Nyman's 1988 soundtrack Drowning by Numbers; or was it the other way around? (I heard Nyman's melodic, Mozart-inspired minimalist score before I saw the pictures, and so had to make my own story up in my head before I knew what the movie would be like). In the event the film was very nearly not a disappointment; it would have had to be very good indeed to live up to the soundtrack, and indeed it was, on a big screen (projector; traditionalist) with good sound and good company (and a good wine) cinema is improved immeasurably. David Lynch has said that it does not matter what form film takes on in the future, as long as these things are present (he did not mention the wine specifically, I do not think that they will serve you wine in most cinemas, but you may be lucky enough to have a projector in your home, in which case it is permissible to encourage your guests to bring a bottle).

|

| Madgett's breakfast |

The director appears to be playing games too - all those that appear in the film, such as 'Hangman's Cricket' were made up for the movie. There almost appears to be some sort of postmodern business going on - eventually life and death themselves become games, and the viewer is invited to arrive at their own interpretation of what it is that it all means; all this painterly symbolism. The cast are actually very good, but the objects and symbols seem to express more than the nuances of their characters ever really could.

There are several lecherous old men in the story. Maidens are pretty, and frolic in the Southwold countryside. We are almost in the world of fairy-tale here, but there is no moral to the story. Ultimately we get up to 100 and the film ends - what more can it do? 'Once you've counted 100, the rest are all the same,' says someone. It's funny - the film is often funny, and sometimes tragic. Bit like life, really.

images: http://petergreenaway.org.uk

Sunday, 5 December 2010

A Thriller Chiller

|

| illustration by Lee Gibbons |

His influence is still felt. Lovecraft knew, for instance, that the most terrifying part of the tale is that before the cause of the terror is revealed, and that fire is not as terrifying as ice. After the Monster is shown, in fact it can seem a bit silly, no more than a cheap special effect. Stephen King and Clive Barker are low-rent imitations next to him, relying on the sensational. Yes, those stories are horrible, once the 'monster' element in them is revealed, but it's a different kind of fear.

He writes everything as if it's absolutely factual. He was interested in forbidden knowledge; he has a way of occasionally inserting something that just conceivably could be true, and this is what gives us pause to question our assumptions about the world. He was clever. He knew how to play on subconsciousness - for one thing, racial fears. He would have recognised King Kong for what it is.

He got many of his ideas in dreams. No writer conveys that feeling better than him. For me, he's also one of the only writers who truly nails the first-person-past-tense. Michel Houellebecq has written a pretty definitive introduction to him for anyone who wants the lowdown, and he seems to have been pretty unhappy, but there's also some of the guy's own material in the book, which would deserve to stand on it's own even if the man himself had been a three-legged Mexican nasal flautist.

I found these images, along with the extract, in an old Games Workshop manual (and how many writers can say they have one of them?), I will take them down if this offends anyone.

THE LAIR OF GREAT CTHULU

Tune: Chattanooga Choo-Choo

Pardon me boy,

Is this the Lair of Great Cthulu?

In the city of slime,

Where it is night all the time.

Bob Hope never went,

Along the road to Great Cthulu,

And Triple-A has no maps,

And all the Tcho-tchos lay traps.

You'll see an ancient sunken city where the angels are wrong.

You'll see the fourth dimension if you're there very long.

Come to the conventacle.

Bring along your pentacle;

Otherwise you'll be dragged off by a tentacle.

A mountain's in the middle, with a house on the peak:

A gnashin' and a thrashin' and a clackin' of beak.

Your soul you will be lackin'

When you see the mighty Kraken.

Oo-oo! Great Cthulu's starting to speak.

So come on aboard,

Along the road to Great Cthulu.

Wen-di-gos and dholes

Will make Big Macs of our souls.

Under the sea,

Down in the ancient city of R'lyeh,

In the lair of Great Cthulu,

They'll suck your soul away!

(Great Cthulu, Great Cthulu -

Suck your soul! -

Great Cthulu, Great Cthulu)

In the lair of Great Cthulu,

They'll suck your soul away.

(Here, there is an obligato saxophone solo, a-la Tex Beneke)

-Joe Carruth and Larry Press

Text & images © 1980-1983 Pentalpha Journal / Games Workshop

Reproduced under fair usage rules, please contact us to remove!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)